Ill-eligible Men

Vietnamese Migrants & Naturalization Applications in Early Twentieth-Century France

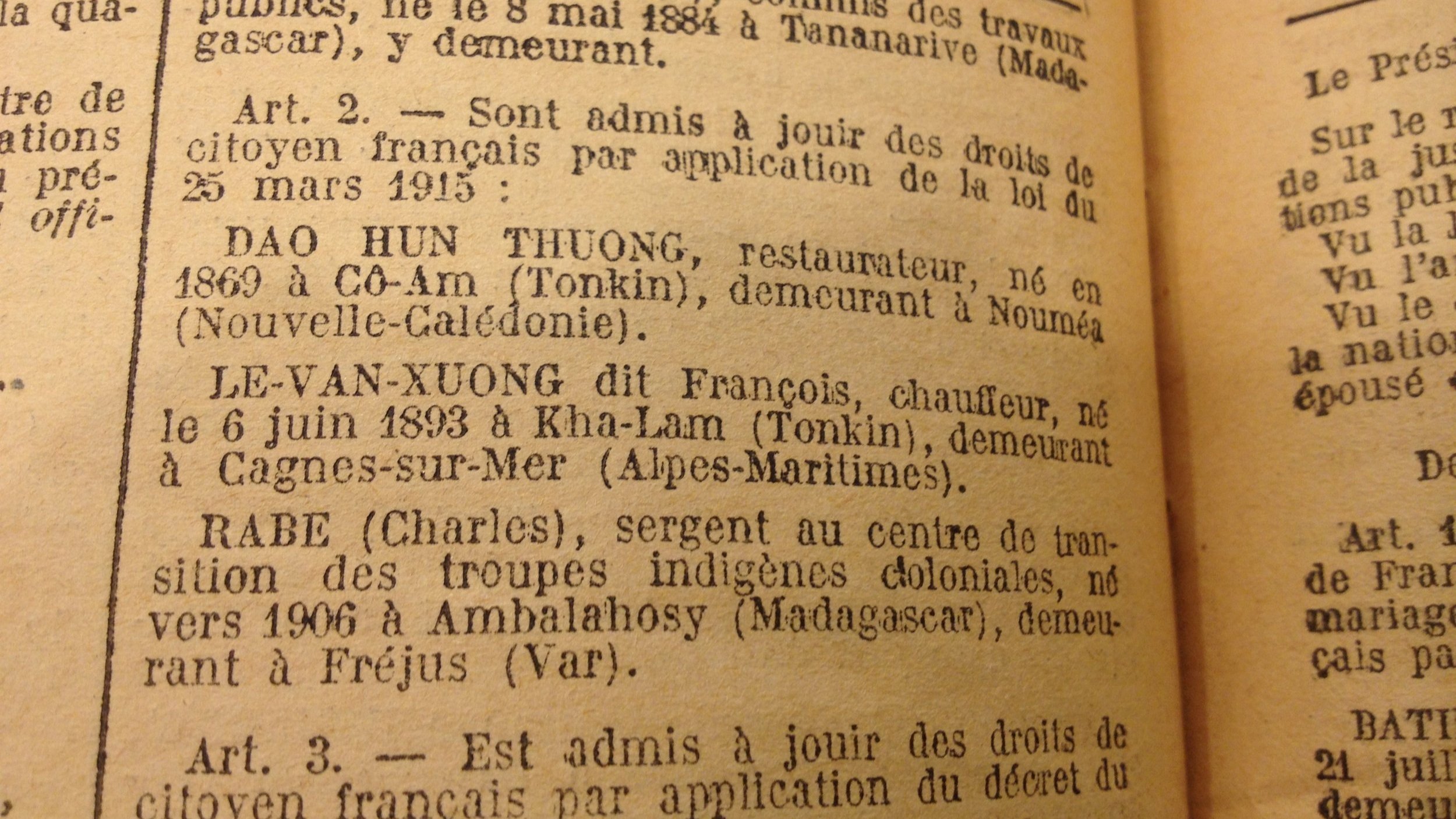

From time to time I came across a sign on a tree: ‘arbre indigène.” This startled me and made me think that the tree had come from Annam. But when I thought about it, I realized that the tree was grown right here. Nevertheless, because the trees were called ‘native,’ I scorned them as miserable, withered specimens that were not worth looking at.Lãng Du in Nhất Linh, Going to FranceNice, 10 o’clock in the evening, August 6, 1929. Hélène Grollimund gave birth. The midwife, 38-year old Louise Brun, presented the baby girl, Suzanne, to husband and now father, Le Van Xuong, dit “François.” From there, man, woman, and child went home, down the Route Nationale, following the fabled blue waters of the Côte d’Azur to Cagnes-sur-Mer, a hamlet of 7,499 residents. While the intimacies of marriage and blood wrought these three into kin, the intricacies of empire divorced them, for on that day, each possessed a different status before the French state. The one whose status the law displaced farthest was Le Van Xuong, a colonial subject. Yet, because he was an eligible man, in possession of this family, he would, like wife and daughter, be called French.

The plot of Le Van Xuong’s naturalization could stand as an illustration of French hospitality. After all, he was a non-white colonial subject who, despite the racial and legal hierarchies of empire, became French. But this interpretation flattens the politics of gender, race, and class in modern France, and forgets feminist and postcolonial critiques of republican universalism. Above all, it neglects the calculus in the process of filling out naturalization applications, reviewing the paperwork, and applying immigration and nationality law. The case of Le Van Xuong and his family, juxtaposed with other Vietnamese male migrants who passed through southeastern France during the 1920s and 1930s, confound theoretical and empirical claims about the power of French republicanism to absorb difference in the name of universal rights. One salient distinction marked Le Van Xuong from the others: his home with Hélène and Suzanne. He was of little utility to the state as an individual, but he was desirable to the state as a man, detached from his homeland in Vietnam, attached to a French woman and child, and settled on French soil. Sources narrate, to the near erasure of his racial origins and legal standing, the state’s attraction to his intimacies with la famille and la terre.

In this article, I argue that during the late Third Republic, the naturalization applications of colonial subjects in the metropole was a deeply precarious and subjective performance. Being welcomed as a non-white foreigner was contingent on representing oneself, on paper, as being associated with a man with a white French family. This gendered and racialized politics of documented respectability shrewdly governed the right of belonging in France.